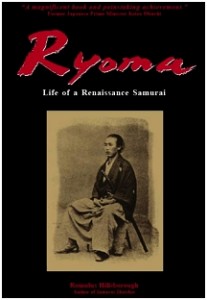

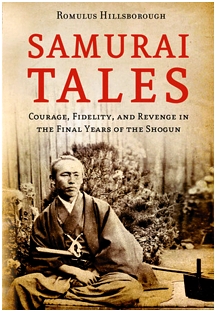

In 1858 the Tokugawa Bakufu, the shogun’s government, concluded its first trade treaties with Western nations including Great Britain, France, Holland and the United States, igniting the “samurai revolution” that would bring about fall of the Bakufu and the modernization of Japan. The trade treaties were opposed by samurai throughout Japan, led by a few powerful feudal domains, including Choshu [present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture]. In the summer of 1864, Choshu, in violation of the trade treaties, militarily blocked the passage of foreign ships through the strait of Shimonoseki, along the vital trade route at the western tip of the Choshu domain, on the main Japanese island of Honshu. In reaction, England, France, America, and Holland dispatched an allied squadron to bombard Shimonoseki – with the tacit approval of the Bakufu. The bombardment began on the 4th day of the Eighth Month of the Japanese calendrical year corresponding to 1864, with the Choshu forces routed in just four days. Following is a slightly edited excerpt from my Samurai Revolution:

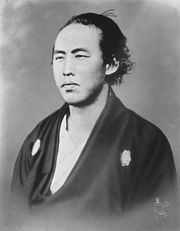

Katsu Kaishu had heard a rumor from Sakamoto Ryoma that Kokura Han, a pro-Bakufu domain located just across the Shimonoseki Strait, had welcomed the allied squadron’s arrival at Shimonoseki, assuring the foreigners that they would not have any trouble from its people. Did the foreign ships attack Shimonoseki at the request of the Bakufu? Kaishu wondered. “Even if Choshu is guilty of crimes,” he noted in his journal, “employing foreign assistance to punish our own countrymen” would itself be criminal. Since “such a crime . . . would be a national disgrace,” the matter must be investigated. [emphasis added; end excerpt]

The president of the United States was recently acquitted for a similar crime by his accomplices in the Senate.

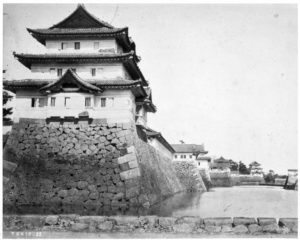

[The photograph of Edo Castle at the end of Tokugawa era appears in Samurai Revolution, p. 488, courtesy of Yokohama Archives of History. Katsu Kaishu is “the shogun’s last samurai” of Samurai Revolution.]