Katsu Kaishū, “the shogun’s last samurai” of Samurai Revolution, was a prolific writer. Recently I’ve been thinking about one of his books, Bōyūchō (“Notebook of Deceased Friends”), which he wrote in 1877 (at age fifty-seven), nine years after the Meiji Restoration, about ten important historical personages of that era. Following is an edited excerpt (without footnotes) from Samurai Revolution:

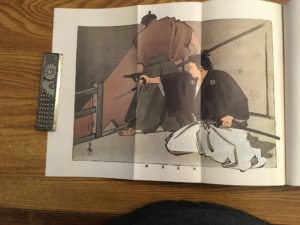

Though Katsu Kaishū had not mentioned Saigō Takamori’s death in his journal, shortly after Saigō died he produced a small book of late great men of the Meiji Restoration. It is clear that Saigō was foremost on his mind—but he could not explicitly dedicate the book to him. Bōyūchō (Notebook of Deceased Friends) is an annotated compilation of letters, poems, and paintings in the original calligraphic brushwork, which Kaishū personally had received from eight late friends “over my career of thirty years.” (The book actually covers ten men, but Kaishū possessed calligraphic works addressed to himself from only eight of them.) . . . . Included beside Saigō are (in order of appearance): Sakuma Shōzan, Yoshida Torajirō (Shōin), Shimazu Nariakira, Yamanouchi Yōdō . . ., Katsura Kogorō, Komatsu Tatéwaki, Yokoi Shōnan, Hirosawa Hyōsuké, and Hatta Tomonori. Yokoi and Saigō are allotted the most space, with three works included from each of them. But Saigō alone is alluded to (if only implicitly) in the Introduction and it was with Saigō’s poem, Zangiku(“Chrysanthemums of Early Winter”), that Kaishū concluded the book.