The alliance between Satsuma and Choshu, concluded in early 1866, was a turning point in the revolution. Sakamoto Ryoma’s biographers never fail to point out that the epochal event was brought about by a political outlaw who considered himself “a nobody.” While Ryoma receives so much of the historical limelight, it must not be forgotten that Nakaoka Shintaro, Ryoma’s cohort from Tosa, also played an indispensable role in bringing about the Satsuma-Choshu Alliance.

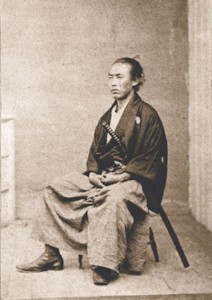

Nakaoka Shintaro

Until the alliance was concluded, Satsuma and Choshu were bitter enemies. But they embraced the same goal: to overthrow the Tokugawa Shogunate. Ryoma and Nakaoka worked for more than a year to persuade their connections in Satsuma and Choshu, namely Saigo Takamori and Katsura Kogoro, to meet. About a year and a half after the alliance was concluded, in the summer of 1867, Ryoma wrote to his sister Otome that Nakaoka “is just like me.” But in many ways they were quite different. Consider the following from Samurai Revolution:

The “man of the sea,” Sakamoto Ryōma, hailed from a “town-samurai” family in the central urban setting of Kōchi Castle Town, situated just inland from the bay that extends outward to the vast Pacific. The “man of the land,” Nakaoka Shintarō, came from the outlying mountains of eastern Tosa. If there is truth in the symbolic association of the wide-open sea with the flexibility of mind and freedom of spirit possessed by Ryōma, and that of the age-old tradition-steeped land with the stoic, rigid nature attributed to Nakaoka, why did Ryōma liken himself to his friend? [end excerpt]

Probably not because both were early members of the Tosa Loyalist Party with close connections to party leader Takechi Hanpeita. Nor because in the month after Ryoma wrote the above-mentioned letter Nakaoka would form and command a land auxiliary force (Rikuentai) in Kyōto, complementing the naval auxiliary force (Kaientai) that Ryoma had organized three months earlier. Nor could it have been because Nakaoka, who, with the leaders of Satsuma and Choshu, advocated the total destruction of the House of Tokugawa by military force, even while Ryoma, just days before writing the letter to his sister, had drafted a conciliatory plan to restore peace to the nation. Nor was it because less than five months after the above letter was sent, Ryoma and Nakaoka would be assassinated together in Kyoto on the eve of the revolution that they had fought so hard to achieve; nor because soon thereafter their graves would be set side by side in the cemetery of heroes on the east side of the city, where they remain to this day. No—Ryoma certainly had something else in mind in likening himself to Nakaoka.

Though Nakaoka, like Ryoma, was originally against opening the country to foreign trade, just before the conclusion of the Satsuma-Choshu Alliance, he wrote a famous letter to friends, in which he reported the changes in his anti-foreign stance in order to learn from foreign nations to develop a “rich nation and strong military.” Nakaoka’s words echo the ideas of Sakuma Shozan (one of the most farsighted thinkers of his time, who in 1850, three years before the arrival of Perry, realizing that isolationism was no longer possible, had advised the Bakufu to modernize in order to defend against Western imperialism) and Katsu Kaishu. Nakaoka had met directly with Sakuma. And though I don’t think he ever actually met Kaishu, he quoted him in the above-cited letter: “Military power depends on the clarity of moral principles, and not on military training or machinery,” Nakaoka informed his friends. “Without the right people, regulations and machines are useless.”

Sakuma was Kaishu’s teacher. Kaishu was Ryoma’s teacher. As such, Ryoma’s thinking was greatly influenced by both of them – as was Nakaoka’s. And therein lies the greatest and most enduring similarity between Ryoma and Nakaoka.

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

For more on the fascinating history of the dawn of modern Japan, see Samurai Revolution.