As a young boy in Los Angeles during the Cuban Missile Crisis, I was overcome with fear by talk at the family dinner table that at any time we all might be blown to smithereens, that Doomsday was just a heartbeat away. As I cried, my parents quoted Shakespeare: “Cowards die many times before their deaths; /The valiant never taste of death but once.” And while those words still ring true, I do not believe that the measure of true courage—moral courage—is limited to the overcoming of fear or even a resolve to die, whether on the field of battle or in mundane everyday life.

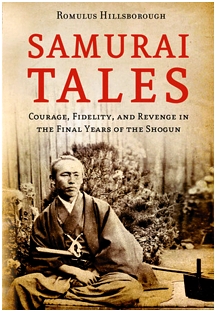

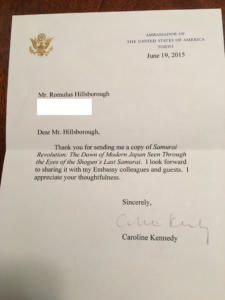

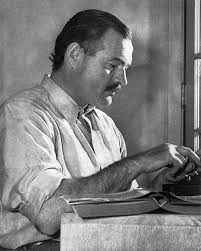

In Profiles in Courage, John F. Kennedy called courage “the most admirable of human virtues.” He quoted Ernest Hemingway’s definition of courage as “Grace under pressure.” Kennedy’s life and presidency were shining examples of that grace—but for JFK it was not enough. He embellished upon Hemingway’s definition, asserting that courage is an unyielding determination to accomplish one’s convictions, regardless of consequence to reputation, career, possessions, body, or indeed life—and usually in defiance of dangerous adversary. [end quote]

In A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. included, on the page before the Foreword, the following famous passage from Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms:

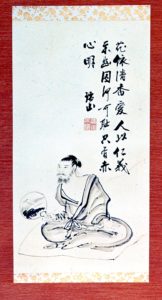

“If people bring so much courage to this world the world has to kill them to break them, so of course it kills them. The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially.”Schlesinger included this passage for its relevance to JFK’s life and death. But, as anyone who has studied the life and death of Sakamoto Ryoma will readily understand, these words of Hemingway also apply to Ryoma as well.

坂本龍馬とジョン・F・ケネディ

「勇気のある2人」

ケネディは上院議員となった3年後の1956年に8名の上院議員たちの伝記と自分の政治家としての信念をつづった「勇気ある人々」(Profiles In Courage)を出版した。その第一章の書き出しに「勇気」を“the most admirable of human virtues”とし、ヘミングウェイが「勇気」を「重圧のもとでの気高さ」と定義していたことを述べた。戦争の英雄でもあり、英雄大統領ともされるケネディの人生そのものは「重圧のもとでの気高さ」の立派な手本であった。でもケネディにとっては「重圧のもとでの気高さ」だけでは満足できず、ヘミングウェイの勇気の定義にもうひとつ付け加えた。「勇気」とは政治家としての名望や職にどんな悪影響が与えられても、自分の財産や身体と命にどんな危険があっても、どんな強い適が前に立っても、自分の信念を果たす断固たる決意にある、とケネディは主張した。

「世に多くの勇気をもってくるなら、この世は彼らを打ちのめすために彼らを殺さなければならない。それで、もちろん、この世は彼らを殺してしまう。この世はすべての人を打ちのめす。そうなると多くの者は打ちのめされた箇所で強くなる。だが、打ちのめされようとしないものは、この世が殺す。それは、善いもの、やさしいもの、勇敢なものを、わけへだてなく、殺す。」(ヘミングウェイ「武器よさらば」高村勝治訳, グーテンベルク21, 1971年)

上記のヘミングウェイの言葉はアーサー・M・シュレジンジャーが「ケネディ――栄光と苦悩の一千日」の前書きの前のページに引用した。ジョン・F・ケネディに相当する言葉だが、もう1人の大人物に も相当する言葉だと私は思う。それは坂本龍馬である。