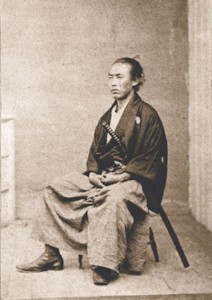

2) Gifted Writer of Prose: Sometime in the early hours of Keiō 2/1/24 (1866), two days after overseeing the conclusion of the Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance in Kyōto, Sakamoto Ryōma was attacked, wounded, and nearly killed by a Bakufu police squad at the Teradaya inn in Fushimi, just south of Kyōto. Ryōma described the attack and his narrow escape in a letter to his family, much of which is excerpted in my accounts of the incident in Ryoma: Life of a Renaissance Samurai and Samurai Revolution.

The attack at the Teradaya and the narrow escape (much to the credit of his girlfriend Oryō, who worked as a maid at the inn) have become legendary through literature and film. Similarly storied are the wedding ceremony between Ryōma and Oryō shortly thereafter, and their subsequent honeymoon (said to be the first in Japan) at the hot springs in the Kirishima mountains of Satsuma, where Ryōma recuperated from his wounds and took a much needed rest. Ryōma, whose myriad talents included a vivid, fluent writing style, described all of this and much more in two letters to his family, both dated Keiō 2/12/4 (1866). The first of these letters, in which Ryōma “took a hard look at a critical moment in his own existence, is a rarity in Bakumatsu history,” Miyaji Saichirō remarked. (Ryōma Hyakuwa, p. 150) Shiba Ryōtarō, whose popular novel Ryōma ga Yuku immortalized Sakamoto Ryōma in the psyche of the Japanese people, called the letter “the first piece of nonfiction literature of the Bakumatsu.” (Qtd. in Miyaji, Ryōma Hyakuwa, p. 152) Ryōma’s graphic account of the attack, I believe, captures the violence of the times as few surviving documents do.

S