This St. Patrick’s Day marks the 162ndanniversary of the arrival of the first Japanese ship to reach North America, as reported in the local San Francisco newspaper Daily Alta Californiaon March 18, 1860:

“His Imperial Japanese Majesty’s war steamer Candinmarru, commanded by Kat-sin-tarroh, a Captain in the Japanese Navy, arrived in our harbor yesterday, and anchored off Vallejo street wharf, at three o’clock P.M., after 37 days’ passage from Uragawa. . . .”

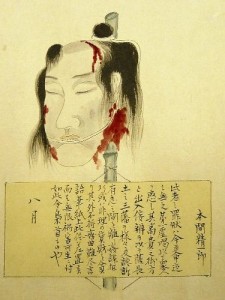

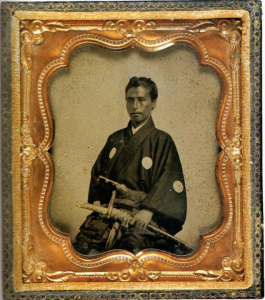

The Daily Alta, of course, was referring to the arrival of the Japanese warship Kanrin Maru, captained by Katsu Kaishū, the “shogun’s last samurai” of my book Samurai Revolution. The American journalists really had no way to know the correct transliteration of the Japanese names, probably because at that early date there was still no standardization thereof—and they certainly bastardized the pronunciation (Katsu Kaishū was his pseudonym; his given name was Katsu Rintarō).

Following is an excerpt from the book (without footnotes):

At dawn of the thirty-eighth day at sea, Katsu Kaishū caught his first sight of the North American continent—and one can only imagine the intense interest with which he took up his binoculars to view through dense fog the coastal mountains in the distance, “like great waves rising above the clouds,” he wrote in a journal-like account of his San Francisco experience in History of the Navy. The captain would have been standing on the deck of his warship—a white banner emblazoned with the red rising sun flying at the mainmast; at the mizzenmast a signal flag of red and white displaying [Admiral] Kimura’s family crest of an encircled diamond. As the Kanrin passed safely through the strait called the Golden Gate, into San Francisco Bay, Kaishū paid special attention to the forts on the north and south shores, for the state-of-the-art military technology naturally concerned the military scientist who would construct modern batteries on the coast of his own country. To this purpose, during his sojourn in and around San Francisco he kept meticulous notes. The battery at Fort Point, on the south shore, he wrote,”is equipped with tens of large guns. The battery is made entirely of brick, with loopholes at three levels. The flat upper surface, sixty or seventy ken [around 109 or 127 meters] in length and of a suitable width, is large enough to mount smaller guns. From the outside there appears to be plenty of room for posting sentries at the rear. On the hillside on the left [north] shore are lights for targeting vessels entering and leaving the bay.”

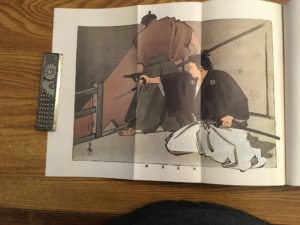

From the topography of the city, “with mountains on all four sides,” Kaishū was struck by “its similarity to our Nagasaki.” Presently, a tugboat approached. “Two of its men boarded our ship. . . . We requested them to lead us [further] into the bay.” “They were going to salute us with cannon fire from land,” wrote Fukuzawa Yukichi, who sailed on the Kanrin as a steward to Kimura. “If they were going to salute us, then we had to return the honor.” But the captain hesitated on the grounds that his tiny ship might not withstand the shock. Meanwhile, Senior Officer Sasakura Kiritarō was eager to return the salute. “No,” said the captain. “Rather than attempting to return the salute and failing, it would be better to let the matter alone.” But Sasakura was determined. “I can do it,” he said. “I’ll show you.” “Don’t be stupid,” the captain retorted. “There’s no way you can do it. But if you try and succeed, you can have my head.” Permission granted, Sasakura ordered some of the men to clean the guns and prepare the gunpowder. He returned the salute superbly, as Kaishū probably expected, assisted by Junior Officer Akamatsu Daizaburō, who used an hourglass to time the intervals between shots. Then Sasakura got his feathers fluffed up and strutted right up to his captain. “Your head belongs to me,” he announced for all to hear. “But I think you’d better keep it where it is for a while. I’m sure you’ll be needing it during the rest of our voyage.” Sasakura’s remark drew laughter from the entire company.