This photo of the Tokugawa family was taken in 1889, about twenty-one years after the fall of the Tokugawa Bakufu, at the home of Tokugawa Akitake (4th from the left), the last daimyo of Mito. Akitake’s elder brother, Tokugawa Yoshinobu (at age 52), the last shōgun, is on the far left. The photo, which includes Yoshinobu’s two sons, a daughter, his mother (a princess of the blood of the Arisugawa family) and other members of his extended family, is on display at the Kōdōkan in Mito. Seated next to Yoshinobu is Tokugawa Iesato, the 16th head of the Tokugawa family who succeeded him after he stepped down as shōgun and family head. Around three years after this photo was taken, Katsu Kaishū, the last shōgun’s “last samurai,” adopted a son of Yoshinobu, Kuwashi, as his heir.

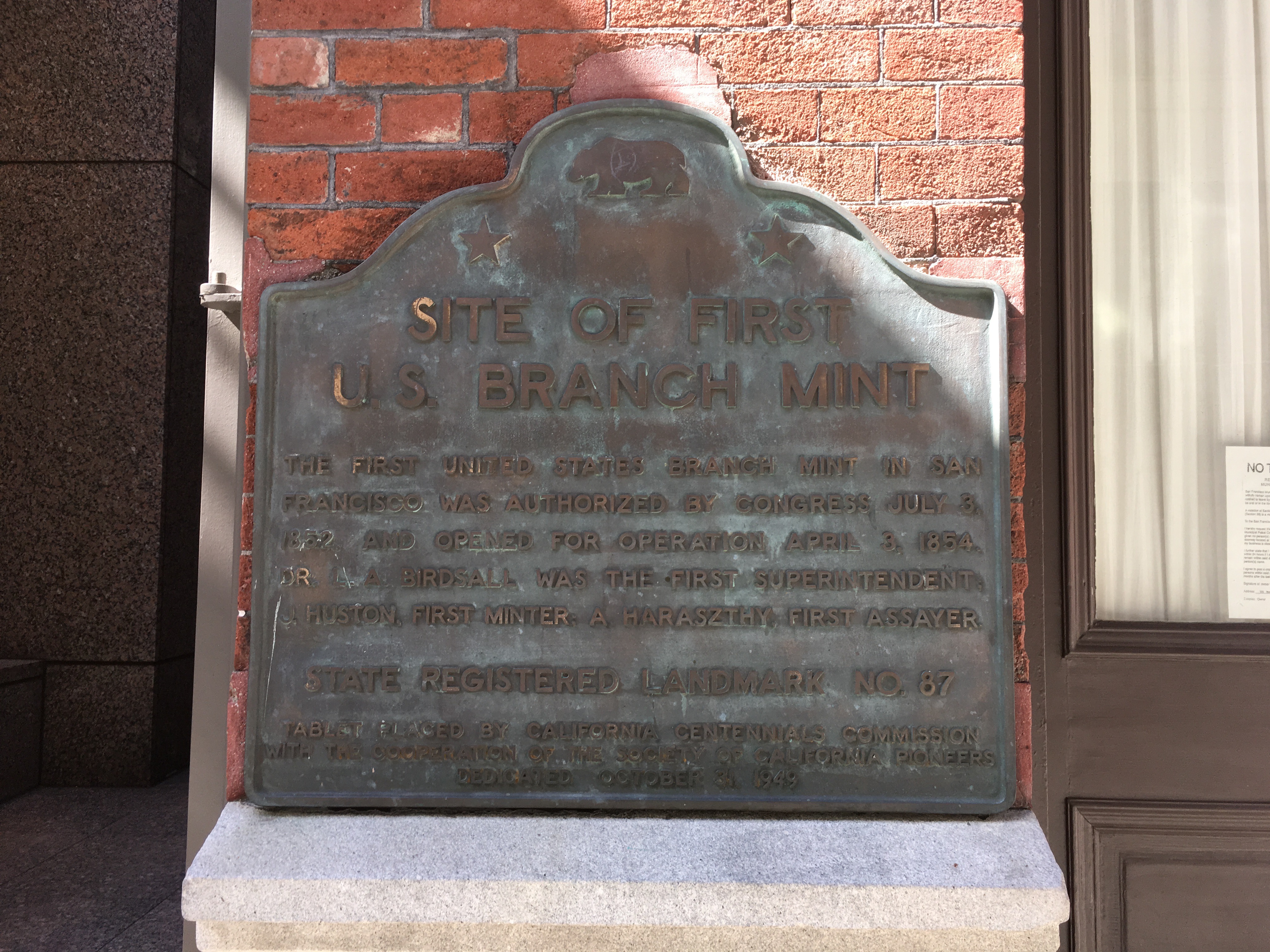

The Japanese warship Kanrin Maru arrived in San Francisco on March 17, 1860, as the first Japanese vessel to reach the United States. The captain, Katsu Kaishu, “marveled at the industrialization of the town,” including “the San Francisco Branch of the United States Mint, comprising a three-story red brick building on Commercial Street . . . ,” I noted in my book, Samurai Revolution, based on a March 21, 1860 article in the local San Francisco newspaper, Daily Alta California..

When the mint moved to a new location in 1874, its building was used by the US Subtreasury for a year, after which it was demolished and replaced by a four-story red brick building, which was gutted in the fire resulting from the 1906 earthquake. It was rebuilt at the same spot on Commercial Street, as the single-story red brick building shown in the photograph above, which I took recently during one of my frequent walks through this district in San Francisco, just east of Chinatown and southeast of North Beach – the old Barbary Coast, a district of “Low drinking and dancing houses, lodging and gambling houses of the same mean class” where “No decent man was in safety to walk the streets after dark,” reports an early history of San Francisco published in 1854,[1] six years before the arrival of the Kanrin Maru. The current building, which houses the Pacific Heritage Museum of San Francisco, retains some of the ambience, I think, of the one that Captain Katsu and company observed. And a cut-away section of the original structure is used as part of the exhibit of the history and significance of the old mint. I’ll say more about Katsu Kaishu and the mean streets of Old San Francisco in future posts.

[1] Frank Soulé, et al. The Annals of San Francisco, pp. 565-66.

Read more about Katsu Kaishu, “the shogun’s last samurai,” in my book Samurai Revolution, the only full-length biography of the great man in English.

The Japanese warship Kanrin Maru, under Captain Katsu Rintaro (aka Katsu Kaishu), landed in San Francisco on March 17, 1860 (St. Patrick’s Day), as the first Japanese ship to reach North America. On March 23 a local San Francisco newspaper reported: “A few of the Japanese are riding about town to-day, looking in at the shops. At Keith’s apothecary establishment they tarried long”—perhaps because on the previous day one of the crew had died of illness. Kaishu’s detailed description of the Marine Hospital in the city, where “eight of our sailors stayed,” denotes his profound interest in modern American medicine.

The eight Japanese sailors were treated for illnesses they had contracted amid harsh conditions at sea. Kaishu wrote that they shared one large south-facing sunny room, where they were well taken care of by the nurses. Three of them, Gennosuke, Tomizo, and Minekichi, from the seafaring province of Sanuki on Shikoku, died at the hospital. They were young men, in their mid-twenties. Kaishu and US Navy Lieutenant John M. Brooke, who with ten other US Navy sailors had accompanied the Japanese on their transpacific voyage, went to the marble yard on Pine Street to order gravestones, and inscribe epitaphs in Japanese and English, respectively, including “the name of our ship, the names of the deceased, and the dates of their deaths,” for the burials that took place in the grounds of the Marine Hospital.

The three graves are still intact, relocated to a cemetery in Colma, just south of San Francisco. The other five ill sailors were nursed back to health, and in August, several months after the Kanrin Maru would set sail on her return journey, made it back to Japan via a ship bound for Hakodate in the far north of Japan.

(In the above photo at the gravesite I am with my good friend Kiyoharu Omino, a distinguished writer of Meiji Restoration history.)

Read about Katsu Kaishu, “the shogun’s last samurai” and his San Francisco experience, in my book Samurai Revolution.

This year marks the 27th year of the era called Heisei in Japanese chronology. Throughout Japanese history new era names have been promulgated to mark an extraordinary occasion or event, such as the enthronement of an emperor. The present emperor, Akihito, ascended the throne in January 1989, upon the death of his father, Hirohito, posthumously called Showa, the name of the era in which he reigned.

Emperor Showa reigned for over 62 years, the longest in an imperial line spanning 125 generations. At his death at 87, he was the longest-living emperor in Japanese history. His funeral ceremonies, including a somber procession which I witnessed among hundreds of thousands of his bereaved subjects gathered in the streets outside the compound of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, were grand affairs befitting a man who during his lifetime had been worshipped as a god.

The Imperial Palace occupies the grounds of the former castle of fifteen generations of shoguns, including Tokugawa Iéyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa Bakufu, the military regime which ruled Japan for two and a half centuries. The castle was surrendered by the vanquished Bakufu to the new imperial government in the spring of 1868, as a result of peace talks between Katsu Kaishu and Saigo Takamori, leaders of the respective sides. After that the illustrious Emperor Meiji, Showa’s grandfather, occupied the inner-palaces of the castle, including the Main Citadel, which had been the residence of the shoguns, and the West Citadel, previously occupied by the families of the shoguns’ sons. These and most of the original castle structures have been lost to fire, including the gate called Sakurada-mon, renowned as the site of the assassination in 1860 of the shogun’s regent, Ii Naosuké, the most powerful man in Japan.

Sakurada Gate was rebuilt during the reign of Emperor Showa’s father. I have visited the site many times. Standing before the gate, I have tried to conjure up in my mind’s eye the scene on that unseasonably snowy morning in late spring over a century and a half ago, when the regent was cut down by a band of eighteen samurai representing Imperial Loyalism. They killed him for his alleged irreverence to the emperor and treachery in having concluded foreign trade treaties without the emperor’s blessing, and his subsequent harsh treatment of feudal lords, nobles of the Imperial Court, and fellow Imperial Loyalists.

Since the palace is located at the city center, one might best visit Sakurada-mon during the still of an early spring morning – and imagine a soft snow falling:

A sudden pistol shot; bloodcurdling screams of the regent’s bodyguards and assailants; the clanging and banging of the tempered steel of their swords; the dull, thick sound of steel cutting through human flesh, then a beheading, men fleeing with the head, others dying – at the onset of an age of terror and the beginning of the end of the Tokugawa Bakufu.

Standing amid a sea of humanity to catch a glimpse of the emperor’s funeral procession, I found myself wondering if the spirits of Ii Naosuké and the others who had died on that day were not among us, to witness that epochal event on that cold winter morning nearly 129 years after the infamous Incident Outside Sakurada Gate.

For updates about new content, connect with me on Facebook.

Ii Naosuke’s assassination is the subject of Part I Samurai Assassins.