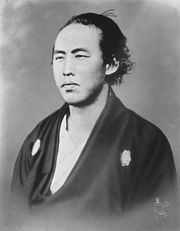

Though Sakamoto Ryoma was the author of the plan for the peaceful restoration of Imperial rule, he was also a leading proponent of Tobaku, “Down with the Bakufu.” These two seemingly contradictory stances underlie the tragedy of his assassination. In a letter to Ryoma the Choshu leader Katsura Kogoro, using the name Kido Junichiro, likened Tobaku to a “Great Drama,” the final act of which was getting underway in Kyoto in the fall of 1867, as Satsuma and Choshu, in collaboration with Court nobleman Iwakura Tomomi, prepared to destroy the Bakufu. With Ryoma’s assassination around two months later, on the eve of a peaceful revolution of his own design, that drama turned tragic.

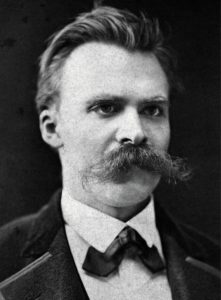

Tragedy may have different connotations depending on interpretation; but perhaps its most widely understood definition is based on the tragic drama of ancient Greece. Nietzsche wrote that Greek tragedy reveals that “the divinity often sends men unjustified suffering, not arbitrarily, but to preserve a customary world-order.”[1] And he held that the horror of tragedy is at the root of its enduring allure—the gist being, as Nietzsche’s English translator Walter Kaufmann observes, that the sublime beauty of ancient Greek tragedy enabled the audience to endure “the utter terror and absurdity of existence.”[2] Ryoma was behind a sea change in Japan’s world-order; and his murder—by multiple sword wounds to the body and a blow to the head from which his brains reportedly protruded even as he was still able to move around and speak—was as unjustifiable as it was horrible.

Julian Young, a Nietzsche biographer, wonder “what kind of satisfaction we could possibly derive from witnessing the destruction of the tragic hero, a figure who, in many respects, represents what is finest and wisest within us.”[3] The answer lies, says Nietzsche, “in the tragic enjoyment of the destruction of the noblest,” with nobility being inseparable from sublime beauty.[4] And to this we should add, as any modern-day moviegoer knows, the pleasure derived from the comfort zone between the viewer and the tragedy unfolding before his eyes.

That the tragedy that is Sakamoto Ryoma’s assassination has endured for more than a century and a half as an allure to historians, novelists, and filmmakers—and indeed a wide segment of the Japanese public—is testimony of the truth of these Nietzschean theories, not least the philosopher’s ideas regarding the destruction of nobility, a quality with which Ryoma was certainly endowed. And Ryoma’s death was truly horrible—for how else describe the butchering of a founder of modern Japan at the dawn of a new era as he was about to finally achieve his dream of engaging in international trade to enable his country to compete with the great Western powers—a dream which had it been fulfilled might well have altered subsequent history to such a degree that future Japanese leaders might not have conceived of the need to create a “Greater East Asia” sphere to counter Western power, a policy that was inextricably entwined with the events leading up to World War II?

[1]Young, Julian. Friedrich Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 41,

[2]Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollindale, trans. The Will to Power. New York: Vintage-Random, 1968, section 1029, note 83.

[3]Young, p. 40.

[4]The Will to Power, section 29.