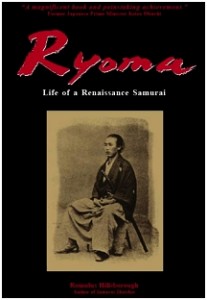

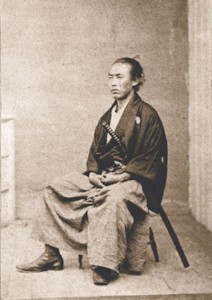

I guess I was most attracted to Ryoma’s personality by his love of freedom. Which was why I dedicated this book to “the spirit of freedom in the soul of man.”

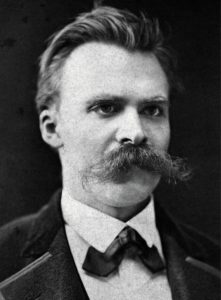

Ryoma was a visionary and a genius—if genius means to conceive of original ideas and to have the courage and audacity to bring them to fruition. His genius, I think, was directly related to his love of freedom. Nietzsche, who was Ryōma’s contemporary, alluded to genius as follows in The Gay Science: “When a human being resists his whole age and stops it at the gate to demand an accounting, this must have influence.” I think this could apply to Ryoma.

Based on his determined resistance to the social iniquities and restraints under the Tokugawa Bakufu and the archaic feudal system, Ryoma influenced “his whole age” through a series of unparalleled historical achievements: Japan’s first trading company, the Satsuma-Choshu Alliance, and his great plan for peaceful restoration of Imperial rule.