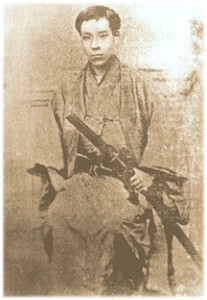

The historical novelist Shiba Ryōtarō wrote that the original purpose of the sword was to kill people, though during the centuries of peace under the Tokugawa Bakufu “it became a philosophy.” With the enactment of the Laws for Warrior Households of Kanbun [Kanbun era: 1661-1673], which included a ban on matches using real swords, kenjutsu (“art of the sword”) was treated in some respects as a sport. Starting in the peaceful Genroku era (1688-1704), many samurai, especially those in Edo, led relatively easy lives as administrators rather than warriors – while form and a beautiful technique took precedence over effectiveness in actual fighting, and theory became more important than ability. But with the renaissance of the martial arts during the last years of the Bakufu (1853-68), kenjutsu practitioners shunned form and beauty for practical technique that would work in the real time.

“Ken wa hito nari” (剣は人なり) goes an old saying. The meaning is cryptic but perhaps may be translated as, “The sword is in the man.” It is used to emphasize the importance of “polishing one’s mind” through rigorous training. This concept is articulated by Katsu Kaishū, who learned how to “polish the mind” from kenjutsu training, he said. Then, “… as long as you keep your mind clear, like a polished mirror and still water, no matter what adversity you might encounter, the means for coping with it will naturally come to you.”

Katsu Kaishū is “the shogun’s last samurai” of Samurai Revolution.

S