Until my Samurai Revolution, the biography by E. Warren Clark, Katz Awa: “The Bismarck of Japan” or the Story of a Noble Life (New York: B.F. Buck, 1904), was the only English-language account (in book form) of Katsu Kaishū (referred to as Katz Awa by Clark), published five years after Kaishū’s death. Clark’s book is more of a hagiographical sketch than a true biography. “HE IS THE MAN (sic) I love – the man to whom personally I owe more gratitude and respect than to any other individual I ever met,” Clark writes of Kaishū. A devout Christian, Clark was one of three American teachers invited to Japan by Kaishū (soon to be appointed minister of navy) in 1871, three years after fall of Bakufu, to help establish scientific schools. Clark excerpts Last Days of the Bakufu, the English translation of Bakufu Shimatsu, written by Kaishū for Clark’s benefit. Regarding Kaishū’s all-important role in the civil war of 1868, Clark asserts that the “surrender of military power on the part of [last shogun] Tokugawa Keiki [Tokugawa Yoshinobu], acting solely on Katz Awa’s advice, was voluntary, patriotic, and immediate.” Contrasting Japan’s handling of its greatest internal conflict with America’s Civil War, Clark lauds Kaishū for having “secured by one stroke of self-abnegation and self-sacrifice conditions of a national unity which we at the same epoch in the ‘sixties’ were struggling to attain in the United States at the cost of nearly a million lives.” Numerous inaccuracies in Clark’s book include the date and city of Kaishū’s birth, and claim that Kaishū served as “president of the naval training school at Nagasaki . . . about a year before . . . Perry’s advent with those barbarian ships” – though he actually served as head of naval cadets at the school several years after Perry’s arrival. Clark also incredulously claims Katsu Kaishū, an exemplar of an ancient society and culture to which Christianity was anathema, accepted Christian faith near end of life.

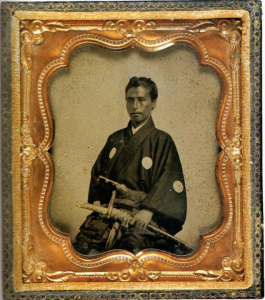

(In 1860, Katsu Kaishū, “the shōgun’s last samurai of Samurai Revolution,” traveled to San Francisco as captain of the warship Kanrin Maru, the first Japanese vessel to reach the United States. The above photo was taken at that time. The scans below are from a September 24, 1894 article about Clark’s visit to San Francisco in a local newspaper.)

S

x

x